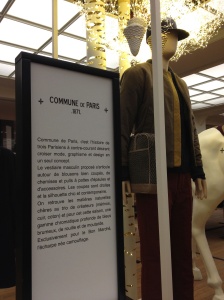

A few days ago, strolling goggle-eyed through the glitz and glam of Bon Marché, Paris’s ultra-upscale department store, I passed a menswear display named for the Paris Commune of 1871. The historical irony smacked me in the face so hard, I nearly got whiplash. To discover that the first worker-controlled state in world history was being used to advertise 350€ ($500) jackets and 50€ ($70) tee-shirts made me want to throw the towel in on this history gig. (Check out Commune de Paris‘ full line here.)

–

What was the Paris Commune? Its story begins in the summer of 1870, when the Second French Empire under the leadership of Napoleon III declared war on neighboring Prussia, whose increasing strength and ambition had been worrying France. And for good reason. Within a matter of weeks Prussia defeated France at the Battle of Sedan, capturing Napoleon III. Paris, however, did not surrender and in September 1870 the Prussians began to siege the city. A period of political chaos and hunger followed.

“Class distinctions of the stomach soon emerged,” in the words of marxist historian Donny Gluckstein. The restauranteurs of the Palais Royal bought the animals of the city zoo, including the elephants Castor and Pollux, to serve to their wealthy customers. Voisin’s restaurant served up an imaginative Christmas feast of kangaroo, antelope, and bear.

–

The ordinary people, meanwhile, could barely afford to buy the cats, dogs, and rats for sale in the city’s streets. Cats were sold at 6 francs each, rats at 1 franc, and dogs at 1.5 francs per pound.

–

The bakers even ran out of flour to make bread. The Musée Carnavelet, in Paris’s Marais district, displays a vitrine containing preserved pieces of “bread” baked during the siege, from a mixture of flour and sawdust.

Rumors circulated that speculators were hiding food from the people, and so it appeared when following the surrender of the city to the Prussians, in January 1871, game, fish, fresh meat, and fowl immediately reappeared on the shelves. Crowds of Parisians looted the markets in fury.

In March 1871, following an effort by the postwar rightist government to seize cannon emplacements on the top of Montmartre, the people of Paris rose up and took control of the city for themselves, instituting a new government based on the principles of mass active democracy and economic equality. “The (literal) bread and butter issue of solving food shortages” were led directly to the idea of the commune de Paris, according to Gluckstein. “If we had the Commune,” one Jacobin newspaper promised, “a cabbage would not cost 100 sous.”

For 72 days, from mid-March through the end of May, the commune governed the city, distributing free food and fuel to the poor, passing a moratorium on the collection of back rents, and reducing salaries for public servants, among other radical acts. The Commune of Paris was devoted to the dream of a world in which nobody lived in luxury while others starved.

The commune was crushed in the end of May by the overwhelming forces of the national government, headquartered in Versailles, in collaboration with the Prussians, who still controlled over half the perimeter of Paris. Parisians built barricades throughout the city to defend the streets, but the communards ended up isolated and without means of communicating with each other.

After the communards were defeated, the Versailles government embarked upon a program of mass executions by machine gun. Estimates of the total killed range up to 37,000, of whom one-fifth were women (who had played a prominent role in the commune).

–

–

To use the memory of these revolutionaries to advertise expensive clothing seems a sad betrayal to me. But I must confess that I have indulged in a little bit of communard-consuming myself. Although I’m not much of a clothes horse, I do like to eat, and so I was excited when a friend suggested we have dinner at Le Temps des Cerises in the Butte aux Cailles (an area of the 13th arrondissement). This restaurant is devoted to the memory of the commune, and is named after a popular song of the time. I believe that Le Temps des Cerises plays host to meetings of the Association des Amis de la Commune de Paris, and it operates as a cooperative.

Perhaps Le Temps des Cerises is slightly more faithful to the memory of the commune than Bon Marché’s clothing line. But I’m not sure that my consumption of a fairly pricey meal there constituted a great act of solidarity with the workers. I was very glad that rat was not on the menu the evening I dined there. The “class distinction of the stomach” was in full force as I enjoyed my appetizer of foie gras and dinner of salmon. I toasted the memory of the commune with a few glasses of wine, and felt thankful, to be a member of the bourgeoisie.

I lived, as a child, on 45 rue de Sevres, right in front of the Bon Marche. Lovely coincidence.

Oh dear. (The Bon Marché display, that is.)

Thanks for turning a fashion retailer’s crass ignorance into a teaching moment.

It also made me think that although painting, dance, and other human efforts to create wonderful things surely emanate from fundamental human urges, only the culinary arts have their origins in a need so primal that it can move history in such a dramatic way.