“Love’s oven is warm” Emily Dickinson wrote to her friend Sarah Tuckerman, on a note that enclosed a gift of slightly scorched handmade sweets, possibly chocolate caramels. If the words were by any other author, one would be forgiven for reading in them a possible sexual double entendre. But Emily Dickinson is enshrined in our memory as the ultimate virgin, the “Queen Recluse” as her friend, the editor Samuel Bowles, described the poet. Dressed always in white, she rarely left her house for thirty years, spending her days tucked away in an upstairs room, writing nearly two thousand poems that few people knew existed until well after her death.

Of course, scholars and fans have long made a cottage industry of identifying Dickinson’s secret failed love affairs: the broken engagement to her brother Austin’s Amherst classmate George Gould; the impossible love for the married Samuel Bowles; the late-life affair with her father’s friend, Judge Otis Phillips Lord. Another school of thought claims her for the queer camp, reading her intense relationships with female friends Susan Gilbert (who later became her brother Austin’s wife), and Kate Scott Turner, as erotic in nature. When a possible photo of Dickinson and Turner surfaced in 2012, The Advocate covered the discovery with the headline “Is This Emily Dickinson and Her Female Lover?”

Yet the queerest thing about Dickinson, to my mind, was her assertive singlehood, her conspicuous refusal to compromise the self through a permanent coupling. She felt the urgency of desire. In one of three famous “Master letters” she wrote to an unnamed lover (or so many people believe), Dickinson described herself as possessed by “a love so big it scares her, rushing among her small heart — pushing aside her blood — and leaving her all faint and white.” Love’s oven was very warm indeed. Dickinson was just extremely restrained about what she baked inside.

Dickinson loved baking for friends and family. She scribbled poems on scraps of paper in her apple-green kitchen between stirrings of the batter. She made gingerbread, decorating the tops with glazed pansies and other small flowers, then lowered the oval cakes in a basket from her upstairs window for the enjoyment of village children. She cooked Federal Cake for Mrs. Lucius Boltwood, and Black Cake for Nellie Sweetser. She told editor (and possible love interest) Thomas Wentworth Higginson that “people must have puddings.”

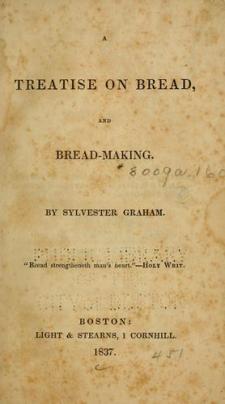

How perfectly in keeping that one of her favorite bakes was Graham Bread, a loaf designed to keep the passions firmly in check. Nineteenth-century sexual-continence advocate Sylvester Graham believed that poor eating lay to blame for most illnesses, and that a diet free from meat, dairy, alcohol, spices, condiments, and anything else likely to stimulate the appetites (gustatory and amatory) was the key to good health. He expressed especial concern about the bread of the modern age, produced from refined flour milled by new equipment and processes that stripped the healthful bran from the wheat. Graham insisted on using “unbolted” flour for his eponymous recipe.

Although, to be clear, there was no single recipe for Graham Bread. Graham was such a vociferous and well-known advocate of the nutritive benefits of loaves made with whole wheat that any such brown bread went under his name by the 1830s. Various websites repeat the claim that Graham’s recipe was “first published” in the New Hyrdropathic Cookbook in 1855 (five years after the reformer’s death). But Emily Dickinson wrote to her brother Austin two years earlier, in 1853, asking “Have you had any maple molasses, or any Graham Bread, since you’ve been away? Every time a new loaf comes smoking on to the table, we wonder if you have any where you have gone to live. I should love to send you a loaf, dearly, if I could.”

Considering that Graham lived in the neighbouring town of Northampton during the 1840s, perhaps the Dickinson family’s recipe was informed by the great man himself. More likely, Dickinson took her recipe from one of the many cookbooks of the age. Eliza Acton published a recipe for Graham Bread in her 1845 volume, Modern Cookery. Acton recommended making the loaf from six quarts of whole wheat meal, one cup of yeast, half a cup of molasses, a teaspoon of pearlash, and a pint of “milk-warm water.” I am not sure whether she had mixed milk and water in mind for this final ingredient, or just water at the temperature of milk when it comes from the cow. The recipe was to be enough to make four loaves, of two pounds each, baked for an hour and a half in a hot oven.

Graham opposed the use of sugar, but even “his” recipe from the Hydropathic Cookbook allows for a tablespoonful of the black syrup per loaf. I find it impossible, however, to imagine that Graham would have approved the use of lard in his bread, as called for by Joseph Lyman in his popular cookbook, The Philosophy of Housekeeping (1859). Lyman was a cousin to the Dickinsons, a frequent visitor to their house during the 1840s, and later a regular correspondent. For this reason, the guides at the Dickinson Homestead in Amherst chose to include Lyman’s recipe for Graham Bread in their 1976 pamphlet, Emily Dickinson: Profile of the Poet as Cook with Selected Recipes.

Graham was as well known for preaching vegetarianism as brown bread, but apparently Dickinson’s cousin Lyman had his own ideas. Lyman’s recipe also includes milk and far more than a tablespoon of molasses per loaf – no word on whether he favored maple molasses, like the poet, or the ordinary variety made from sugar cane. (As an aside, maple molasses sounds amazing. I wonder if the poet meant molasses refined from maple sugar, popular among antislavery families, or whether she had in mind some combination of maple syrup and molasses, which also sounds super tasty.)

Reading Lyman’s recipe, I couldn’t shake the sense that his inclusion of generous portions of such tasty ingredients as molasses and lard were intended to counterbalance the loaf’s otherwise unappealing properties. A dough made entirely from the roughest unsifted wheat could not help but yield a heavy loaf. Several nineteenth-century cookbooks report that Graham Breads were best eaten fresh out of the oven. Notice that Dickinson reminds Austin of the pleasures of home by picturing a loaf still smoking on the table, not hardened and cold the following morning. Graham loaves reputedly developed such hard exteriors with time that the crusts could only be eaten if they were dunked first in coffee or tea. On the bright side, these thick shells helped preserve the loaves from spoilage.

Bearing these red flags in mind, I saw in the words of “Dickinson’s” recipe an unparalleled opportunity for another historic kitchen disaster. And with le rosbif away for work for the week, I could use an aid to keep my appetites in check. So, like the poet herself, I hauled out the mixing bowls and ingredients.

I began by combining a gill of molasses, half a gill of lard, and a teaspoon of salt. (For gill, read cup.)

After beating the two together with my historic orange silicone spatula, I added 1 ½ cups of warmed milk. The recipe suggested between 1 ½ and 2 cups. In retrospect I wish I had added the full two cups, it may have made for a more pliable dough when, after mixing in my gill of yeast (two and a half tablespoons, activated in a quarter cup of warm water with a tablespoon of sugar), I next added a full two quarts (8 cups) of whole wheat flour. I thought about adding extra bran for effect, but we were out and besides, the flour I used was plenty full of roughage.

In fact, the mix was so full of roughage I had a hard time getting it to come together. Eventually I got there, sort of, then left the dough at the bottom of my mixing bowl to rise overnight. Which it did, sort of, but not enough to facilitate the kneading. Pounded down the next morning, the dough remained so stiff and noncompliant that our super-powered mixer nearly broke when I tried to put it to the work. Le Rosbif, who had called in to say good morning to the children, nearly cried at the sound of his beloved machine straining its engine to subdue my impossible mix. There was no choice but to turn the dough back out onto the counter, roll up my sleeves, and set to working by hand. Actually, I had to work the dough with elbows and forearms, my hands – more used to tapping keys than kneading bread – being unequipped to the task. The exercise gave me a new perspective on the physicality of Emily Dickinson. She seems so ephemeral in her eerie white dress, but the woman must have been tougher than she appears in our memory. I like to imagine her grunting with effort as worked the family’s daily bread.

I was more than worn out after half an hour of banging and battering. I decided to let the dough sit for another hour’s rise. Then finally I dropped the risen loaf into a cast-iron Dutch oven, which I slid onto a stone in love’s warm oven. The bread smelled wonderful as it baked, which almost seemed compensation enough for the enterprise, regardless of how the loaf tasted when it came out. After an hour (the recommended cook time), I pulled the bread from the oven. It had developed a thick dark brown crust, and when I knocked the bottom it sounded hollow enough.

Those who know something about baking bread might be interested to learn that the final loaf came in at four pounds, which I cooked in a 375 degree oven for an hour. In other words, I didn’t cook it enough. As a diligent fan of the Great British Bake-Off, I could picture judge Paul Hollywood’s withering gaze as he tore a hunk of dough from the middle of my bread, scrunched it up into a tight gummy wad, and pronounced my fabulous creation ‘raw inside.’ Once again, I count myself lucky not to be a contestant. Because, undercooked or not, the bread in fact tasted pretty good. Warm and buttered, with a little leftover salmon flaked on top, and a sprinkle of salt, it made a fine lunch. I am sure that the other three and three-quarter pounds will taste great toasted over the next few days as I await le rosbif’s return.

Unfortunately the kids will not be helping me gnaw my way through this monster. Eli was mildly intrigued when he thought the loaf might be close in resemblance to a graham cracker, which he can appreciate crunched up into cheesecake crust. But upon learning the truth of the matter he turned a disdainful nose at my creation. (For the record, he’s not such a great fan of graham crackers either. Earlier this week when I packed a couple in his lunch, I received a terse text at “nutrition break” that read simply, “gram [sic] crackers really?” I replied that a child who was old enough to text complaints about his lunch was certainly old enough to pack his own. That put an end to the conversation.)

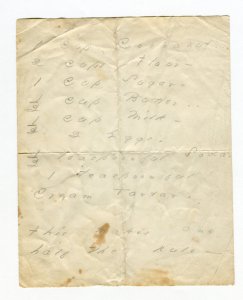

Back to the monster loaf: in my defense, Dickinson herself may have encountered kitchen disaster with Lyman’s recipe. Three decades after she first wrote to Austin on the subject, the poet turned to another cousin, Frances Norcross, for a different recipe for the hearty loaf. “Mother heard Fanny telling Vinnie about her graham bread. She would like to taste it,” Dickinson beseeched. “Will Fanny please write Emily how, and not to inconvenient? Every particular, for Emily is dull, and she will pay in gratitude, which, though not canned like quinces, is fragrantest of all we know.” Frances apparently complied with the poet’s request, for a follow-up letter reported that “the bread resulted charmingly, and such pretty little proportions, quaint as a druggist’s formula – ‘I do remember an apothecary.’ Mother and Vinnie think it the nicest they have ever known, and Maggie so extols it.” We can only assume that Dickinson was in earnest, although her apothecary reference, drawn from the Shakespearean scene in which Romeo acquires his death draught, hints at a possible irony. But one has to be careful with reading double entendres into Emily Dickinson’s glorious imagery. That’s what got me into this trouble to begin with.

I just came across your blog entry as I was googling Emily Dickenson recipes. Your work with the dough reminded me of when I tried to make bagels and was obsessed with putting as little water in as possible which made the dough unworkable. When I finally relented and re-did the recipe with more water, everything worked much better. So, I think you are correct that a bit more milk would have fixed things. I have sinced learned that when you are making bread, you add the flour in gradually, so that you can adjust for moisture content, it being easier to add more flour as you are kneading than to add more liquid.

Thank you for this article. I enjoyed it very much and am looking forward to going through the rest of your blog. I enjoy historical recipes very much and have been astounded in the last month at how many other people are also interested and writing about it!

I enjoyed this very much and it made me think of Margaret Rudkin, whose lovely Pepperidge Farm Cookbook I acquired a while back and have been dipping into for work this month. She doesn’t mention Graham or his 19th century peers but she was an avid cookbook collector and recipe scholar and loaf on which she founded her baking empire. She had never done yeast cookery before she first tried to make wholewheat bread, yet she soon ‘invented’ n a recipe that added “butter, milk, molasses and honey” to the mix, leading to soft tasty bread the whole family wanted to try.

Rudkin also says that, at least in her upstate NY locale, whole wheat and later unbleached white flours were so hard to come by that she had to re-open the dormant mills on the farmland she and her husband had bought years before.

PS Paul Hollywood’s bread and criteria for excellence therein often upsets me. I still prefer Dan Lepard for full-spectrum baking gurudom.

Reblogged this on mauriziocanetta.

Reblogged this on .

Reblogged this on ohmerogod.

When I was in high school my fellow classmates in English class suggested I was like Emily Dickinson based on a few poems I had written for our class publication. That year I learned to bake bread emulating the fabulous abilities of my grandmother. She always suggested that purely whole wheat bread was hard to make and to always add about 1 cup white flour per every three of whole wheat. One time I made whole wheat and I had no white flour but I had started so I finished it. It was very dense but tasty with only a little honey. I agree regardless of what kind of flour one must gradually add the last two cups of flour. I know my recipe called for 1/3 cup oil so it couldn’t be called Graham bread. I still write poetry. Some are on my blog. No I am not celibate.

I never really wanted to emulate Emily. 🙂 I like this post as it brought with it interesting memories.

I live by her words “I dwell in possibility”. Loved this. Thanks!

Wait, Dickinson the poet? If it is I’m laughing.

I love this so much. Fantastic writing! Thanks for sharing.

Reblogged this on antelosrilanka.

Awesome post. I just love the way you wrote it.

I remember Emily’s Dickerson’s poems, back when I was in high school, we studied, different, authors especially those writing poems. I didn’t realize she wrote recipes, and made them. I enjoyed your post, it brought back good memories. Deb

I love that you were inspired by Emily Dickinson to bake! That is one heck of a loaf of bread 🙂

I have no idea how I stumbled upon this earlier today. I’m returning to it shortly before bed, and what a read! Thank you so much. As a wild yeast, whole wheat sourdough bread maker, I will definitely be sharing it.

This is such a cool idea!

Reblogged this on nysstalgia.

I love this so much

Thanks for the trick to add more liquid!

I came across your article while testing Emily’s coconut cake – it went down well with testers. I hope to bake some of her recipes for the launch of my cousin’s book “Miss Emily” . Her fictionalised Dickinson story includes chapters where Emily bakes (If you are interested it is already out in the US – http://www.amazon.com/Miss-Emily-Novel-Nuala-OConnor/dp/014312675X/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1438202344&sr=1-1&keywords=miss+emily ).

sounds great – good luck to your sister!

I really loved the way you wrote this! ♡

Reblogged this on bobfernandes03.

Reblogged this on bigred1701.

I love how your blog is focused on how Emily Dickinson focused on all forms of art,especially cooking and how she

“scribbled on pieces of paper” while baking.

Lovely write.

Reblogged this on piercejo.

Reblogged this on Mi versión en diminuto.

I enjoyed reading this! Thank you.

Reblogged this on Sarah's Attic Of Treasures and commented:

A Bit of History. Emily Dickinson

From Rachel Hope Cleves. December 11, 2014

This was a great read! I like reading Emily Dickinson poetry. This bread sounds intimidating to make, lol. I only bake challah bread, + my recipe is pretty easy.

I never knew Graham Crackers were linked to Emily Dickinson. And she is one of cult favourites in Literary icons. Hallelujah! The day I join wordPress, is the day I learn this connection. And I was thinking of baking bread, for next week, I have made a Spanish week program. The menu for the table will be Spanish cuisine. This is more than a coincidence. I think, the Bacchus is giving me a sign to bake bread at the earliest.

Where great poetry can meet everyday life. Great topic idea and very well researched and written. Bravo!

Reblogged this on poetrymetafisica.

Literature, history, and baking? Be still, my heart! Great post.