The novel most responsible for the everlasting romanticization of Jazz Age expat culture in Paris, Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, takes place half in Spain. When the pressures of drinking wine and eating oysters in the cafés of Montparnasse became too much to take, Hemingway, his friends, and the characters he modelled after them, escaped to San Sebastián, a beach town on the Bay of Biscay ten miles across the border from France, or to Pamplona, a little further south, where they watched the bullfights.

Alice B. Toklas loved Spain as much as Hemingway. She would have lived there, if Gertrude Stein had agreed, in the town of Avila west of Madrid. “I immediately lost my heart to Avila,” Stein has Toklas recall in the Autobiography, “I must stay in Avila forever I insisted. Gertrude Stein was very upset, Avila was alright but she insisted, she needed Paris.” Stein, of course, got her way, still the couple traveled many times to Spain where Toklas made an odyssey of collecting gazpacho recipes. She included seven in her cookbook, four from the Spanish cities of Malaga, Seville, Cordoba, and Segovia, and three related soups from Turkey, Greece, and Poland. One day I would like to have a potluck where each guest brings one of Toklas’s soups and we can taste them all in comparison.

Unfortunately, Toklas did not include a recipe for salmorejo, a gazpacho-like soup originating from Andalusia, which I ate side-by-side with un auténtico gazpacho the other night at Francisco Lillo Roldán’s tasting room La Oliva, in Granada. We too have temporarily escaped Paris for Spain, following not the examples of expats past, but the dictates of the French school calendar and the vagaries of chance. Paris schools have broken up for the Toussaint holiday and we are lucky enough to have friends living in Granada, in the extreme south of Spain, whom we can visit. It’s t-shirt weather here, glorious blue skies, hardly a breeze to prickle the skin. I can understand why so many Paris-dwellers before me, tired of the grey chill, have flocked to Spain for the sun.

The inexpensive wine was also a lure in Hemingway’s time – Jake Barnes in The Sun Also Rises buys a leather wine-skin that holds five litres, which he fills for a couple pesetas. Truth be told the cheap wine was a pretty powerful lure for me as well. A glass of white in one of Granada’s many bars costs only 2€ and comes with a free plate of tapas, Spanish ham if you’re lucky. If you’re unlucky, as we were last night, the tapas could be a plate of cold overcooked spinach rotini sauced with ketchup and mayonnaise. This might explain why most people don’t come to Spain for the food (except for the extremely wealthy who made the pilgrimage to El Bulli when it was still open, or to the michelin-starred restaurants of San Sebastián today). What I remembered from my only previous trip to Spain, fifteen years ago, was lots of fried food and the rare un-fried food drowned in as much oil as its counterpart. I did have one magical paella at a restaurant in Barcelona (selected by the same sophisticated friend who chose our cassoulet restaurant in Carcassonne). But otherwise, like the Lady Brett Ashley in The Sun Also Rises, I took the majority of my calories in liquid form.

If Spain is not necessarily reputed for the excellence of its ordinary cooking, there can be no doubt about the quality of its ingredients. We visited the mercado on my first morning in town, and came home with bags full of ripe tomatoes, peppers, eggplant, pears, and lemons. There’s so much ripe fruit on the trees throughout town it falls bursting on the street, no one can eat it fast enough. Slicks of ripe persimmon staining the pavement, pomegranate seeds erupting from their skins, grapes wizening on the vine, and oranges on the trees, Andalusia in mid-October is a garden of paradise.

And then there’s the ham. Spanish jamón is so fine it’s exported around the world. We can buy it across the street in Paris at the Carrefour. In fact the French seem to prefer it to the Bayonne ham, produced in France just across the border from San Sebastían. But nothing I’ve eaten in France compares to the jamón I tasted the other night at La Oliva.

Again, thanks to a canny friend, I had the perfect dinner reservations, not at a restaurant but at a tasting room run by Francisco Lillo Roldán, who owns a shop in town where he sells oils, cheeses, meats, wines, and other Spanish products. A couple years ago he began offering evening tastings of ingredients in his shop, accompanied by explanations in English and German for sunburned vacationers about the products and Spanish food. The popularity of these evenings led Francisco to seek out slightly larger premises in the cave of a downtown boutique hotel where he could host nightly dinners. He prefers not to call La Oliva a restaurant, since the focus is not on fine cooking but on the raw materials, presented very simply. There were thirteen courses spread out over three hours the evening I went, with many courses incorporating multiple tastings, and five matched wines as well. And yet I left not feeling overstuffed, because the food had not been prepared with the butter, cream, and meat stocks that give French food its richness.

The menu focused on tasting by bringing like things into comparison. We began with three olive oils, one sweet, one bitter, and one blended. Next we had five patés – partridge, cheese, cod, ham, and tomato – daubed on little crackers. We had the gazpacho and the salmorejo side by side: the gazpacho much more of a “liquid salad” as I saw it translated on a local menu, a thin tomato water with small cubes of vegetables in it, and the salmorejo a proper soup of tomatoes thickened with bread crumbs. There were five cheeses, and five torrones to end with. In between were simple prepared dishes: swordfish with parsley and a slice of boiled potato with paprika, avocado salad with parsley and a chopped shrimp, a stewed rice with shrimp stock, pork salad in a lettuce leaf, and salt cod mixed with pomegranate seeds, or as Francisco pronounced the English name for this fruit: pomme-grenades, giving me the image of exploding apples, a very apt analogy for the way that pomegranates burst on the branch if left unpicked. (The Spanish word for pomegranate, of course, is granada. It is the symbol of the city, and possibly the origin of the city’s name. There are pomegranates everywhere in Granada,)

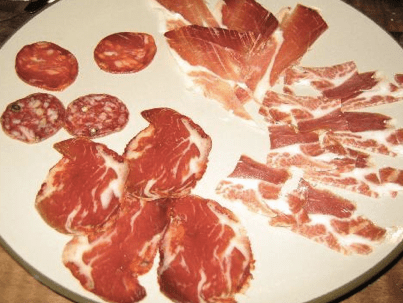

And then there was the plate of Spanish jamón, five varieties: Ibérico, serrano, lomo, chorizo, and salchichon. The highlight of my meal for two reasons. First, of course, the flavor. The hams were so tender, so meaty, so different from each other. My favorite was actually the lomo, which was intensely nutty. It was without a doubt the best Spanish ham I have ever had. The other reason this course made a profound impression on me had to do with Francisco’s explanation of what we were eating.

Isn’t it true, a very cultured man sitting on my right asked Francisco, that Ibérico hams taste different from serrano because the pigs eat only acorns? Francisco took a seat. The force of his feeling in response to this question dropped him. It is not an exaggeration to say that he grew close to tears as he answered:

Forty years ago there was no Ibérico or serrano, there was only jamón. You didn’t have to name the ham, because it came from Elena or someone else you knew. And people knew that every ham was different. There were so many things that might affect the flavor of a ham, from the curing process, to the conditions it was raised in, to the food it ate. Today, bureaucratic regulations strictly define what constitutes an Ibérico – exactly what percentage of the pig’s genes must be Ibérico, exactly how much of its weight must be put on through eating acorns. But this formalization of production rules distracts from the most important point, which is flavor. The difference in flavor between a male pig and a female pig may be far more profound than exactly how many pounds of acorns the pig had consumed. The only way to judge a ham is by taste.

In other words, this man who devotes his life to the promotion of Spanish “products” completely rejected the fetishization and commodification of taste. I don’t mean that he rejected either the celebration of good-tasting foods or making money through selling food. What he rejected was 1) the orientation towards gastronomy as a field of esoteric knowledge that itself constitutes refined culinary pleasure, as if knowing the number of acorns that an Ibérico pig must consume creates the enjoyment of eating its ham; and 2) the standardization of food, like ham, into modern industrial commodities defined by regularity, as if taste could be so easily determined by the number of acorns a pig eats.

To combine a love of the taste and history of local foods with such a passion against their commodity-fetishization must be profoundly difficult. I found Francisco’s point extremely interesting, but I was not sure that it made much on an impression on the fellow who asked about the acorn-consumption of Ibérico pigs in the first place. Francisco’s clientele of privileged international travellers, and here I must include myself, are those people most likely to relate to food as something to be known and then tasted. Francisco doesn’t want his guests leaving the table with a refined knowledge of the differences between Ibérico and serrano, but with a memory of pleasure in tasting all the different hams on the plate. Or not, as Francisco kept telling us: you don’t have to like everything you taste.

But I did enjoy everything, I enjoyed this meal more than any other elaborate tasting menu I’ve ever had. I haven’t tried very many, it’s true, maybe three others? Despite the reputation this blog is giving me for being a foodie, I’ve never eaten out all that much, particularly not at expensive restaurants. I never had the money: I went to graduate school when I was twenty-three and had my first child when I was twenty-five, in other words I completely missed the money-making childless decade enjoyed by most middle-class professionals. And moreover, the few times that my husband and I did splurge on uber-high-end restaurants we mostly didn’t enjoy the meals. The food might have been beautiful and elaborate but it didn’t always taste good and the richness often made me feel sick afterwards. There are some who complain online that La Oliva is not really a restaurant. There is no fine cooking to be had there. But for me, this was the perfect way to enjoy Spanish food.

Leave a reply to Gloria Trujillo Cancel reply