Thelma Ellen Wood was stupendously tall, sexually irresistible, and a wonderful cook with a propensity for rum and coke. Many authors who crossed paths with Wood wrote lavish accounts of her body as a dish, but none bothered to record her favorite recipes.

–

Most readers encounter Wood through the eyes of her jealous lover Djuna Barnes, whose best-known novel Nightwood (1936) tells the story of their tumultuous affair in 1920s Paris. Wood, called Robin Vote in the novel, makes her first appearance in its pages dead drunk, but even in this state she exerts a powerful magnetism. Barnes pictures her flung across a bed “heavy and dishevelled. Her legs, in white flannel trousers, were spread as in a dance, the thick lacquered pumps looking too lively for the arrested step.” Her body exhales a perfume of earth-flesh, fungi, and oil of amber. Her eyes are a “mysterious and shocking blue” with “the iris of wild beasts who have not tamed the focus down to meet the human eye.” She is half beast, “we feel that we could eat her.”

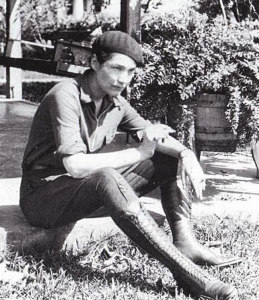

Barnes’ shift to the first-person plural we seems apt, since so many people felt the same overpowering attraction to Wood. She appealed to a surprising cross-section of characters – from femme women like Barnes (who once claimed “I’m not a lesbian, I just loved Thelma”), to butch men like author John Ferrar Holms, to femme men like poet John “Buffy” Glassco, to butch women like photographer Berenice Abbott. Six feet tall, “with the body of a boy” (in Barnes’ words), an intense stare, and an ungainly stride, Wood excited most everybody she met.

–

Glassco, a bisexual Canadian poet who claimed to have slept with everyone from Alfred “Bosie” Douglas to Margaret Whitney, recalled an evening spent with Wood in his gossipy Memoirs of Montparnasse. Glassco met Wood, “a tall, beautiful, dazed-looking girl … who had the largest pair of feet I have ever seen,” at La Noctambule, a bar on the rue Champollion in Saint-Germain. According to Glassco, he soon propositioned Wood and the two escaped into the night, Wood barreling her way through the streets of the Latin Quarter: “her way of dealing with the crowd on the sidewalk,” writes Glassco “was to plough straight ahead; when she struck or jostled a passerby she merely staggered, shook her splendid shoulders, regained her balance, and moved forward.” After several drinks at a workingman’s bar, Wood invited Glassco to join her at a brothel in Montmartre. Despite his discovery that Wood “was a very bad dancer,” Glassco found “the thrill of holding this beautiful big body made up for everything. I confined myself to marking time and avoiding her large feet, which was not difficult since the awkward movements of her hips telegraphed their position with perfect accuracy.” Eventually, Glassco claimed, the two hired a private room at the brothel, where Wood took off all her clothes and stretched out on the bed with her eyes tightly closed. “I had never seen a more beautiful body,” Glassco concludes, “to find it frigid was a great disappointment.”

Most of her lovers did not find Wood frigid. Djuna Barnes thought her “the great sexual treat of the world,” according to John Ferrar Holms, lover of modern-art patron Peggy Guggenheim (whom Wood had once propositioned on her knees). Holms himself was equally impressed by Wood’s sex appeal. “The obvious thing about Thelma was sexual vitality,” he observed to the diarist Emily Holmes Coleman, “she was made for fucking.” Coleman described Wood as looking like “an old greyhound,” “a doughy cat,” and an “amoeba feeling about with stumps,” but nevertheless she felt a powerful attraction to Wood, who once pulled Coleman between her legs and called her a servant to art. What a pick-up line! “She makes one want to make love,” Coleman sighed.

–

Robert McAlmon, the bisexual novelist and editor, lover of Buffy Glassco, and good friend of Djuna Barnes, described Wood in his roman à clef The Nightinghouls of Paris as a “handsome boy-girl with a boy’s predatory curiosity.” Barnes, of the same opinion, almost titled her novel about Wood “Night Beast.”

But for all the depictions of Wood as a wild butch seductress, she had a surprising domestic side as well. Djuna Barnes couldn’t boil an egg, but Wood cooked excellent meals for her lovers and friends. Most historical accounts emphasize Wood’s creative work as a silverpoint artist, but food seems to have been her true metier. After the affair with Barnes came to its bitter end, Wood lived in Connecticut where she tried to run a gourmet catering business, although her crippling alcoholism got in the way. Another time she joined forces with Edith Annesley Taylor, a former lover (who had also been a lover of the Armenian mystic George Gurdjieff), to launch a business selling herbs and exotic foods. This enterprise failed too.

Unfortunately, the sources don’t reveal what Wood liked to cook. Wood didn’t leave her own account of her life, and those accounts written by the men and women knew her are too consumed with looking at Wood’s body to give attention to her creations. A sketchbook of hers is archived within the Djuna Barnes collection at the University of Maryland, and perhaps its numerous pictures of Paris café society give a hint about the artist’s tastes. I imagine they were as omnivorous as her sexual predilections.

Leave a reply to The Rendezvous of Epicures: New York | The Not So Innocents Abroad Cancel reply