I fell in love with Charity and Sylvia, the subjects of my last book. And I feel seduced by many of the figures of my new research, including problematic characters like Norman Douglas, a pederast as well as an epicure. But I will never fall for Raymond Duncan, who was not only a megalomaniac, but who also preached the doctrine of voluntary restriction and claimed to be satisfied with a dinner of lettuce and turnips. Raymond Duncan was a creep, which makes me happy, because as pleasing as it is to research people you love there’s also great fun to be had from writing about villains.

I first encountered Raymond Duncan in Kay Boyle’s and Robert McAlmon’s joint memoir Being Geniuses Together, 1920-1930. Boyle was not a fan, to put it lightly. After leaving her first husband for her tubercular lover, the poet Ernest Walsh, who got her pregnant then died before the birth of their child, Boyle moved to Paris in 1928. She was a struggling writer with a young child and no spouse, unable to make ends meet, when she met Raymond Duncan, who had a communal compound in Neuilly, on the western outskirts of Paris, north of the Bois de Boulogne. When Duncan invited Boyle and her child to come live in Neuilly, it came as a godsend. His accounts of how the members of the community drank fresh goat milk from wooden bowls and lived in simple harmony with nature sounded idyllic to Boyle. But, no surprise, Neuilly did not turn out to be all Duncan promised. Within a year, Boyle was forced to kidnap her own daughter and to flee Paris under cover of night to escape from Duncan’s clutches.

Who was Raymond Duncan? If he is remembered at all, it is as the older brother of Isadora Duncan, the famous modern dance innovator who died tragically in 1927 when her long flowing scarf got caught in the axel of an open-top car she was driving in and her neck snapped. My mother, in her motherly cautiousness, used to warn me not to let my winter scarves trail when I was a child: because look what happened to Isadora Duncan! Before her dramatic death, Duncan was famous for transforming the world of dance with her bare-footed, uncorseted, free-form choreography inspired by the figures in classical Greek pottery and statuary.

–

As it happens, reviving the Greeks was a family business. Isadora was one of four siblings born in San Francisco to an artistic mother who, following a scandalous divorce from their banker father, raised her children to be artists. Mother and children travelled to Europe in 1898, Isadora pursuing a career as a dancer, and Raymond moving to Greece and marrying Penelope Sikelianos (her brother, the poet Angelos Sikelianos, later married Eva Palmer, a bisexual American heiress, who had once been Natalie Barney’s lover). Together, Raymond and Penelope (along with Eva and Angelos) promoted a return to the classical Greek lifestyle, building a villa outside Athens where they hung tapestries on the wall and forbid visitors to enter wearing modern dress.

Soon Raymond, Penelope, and their son Menalkas moved to Paris (Neuilly), where Isadora had become a great success, and where their appearance made an immediate impact. It’s not hard to see why the Parisians were excited by the Duncan’s appearances, and particularly by the appearance of Raymond himself. Since 1903, Raymond Duncan had rejected modern clothing in exchange for togas, draped from hand-woven textiles, that left his arms entirely bare. To complement this garb, Duncan wore his hair long, past his shoulders, tied back with a silk band around his forehead. And all through the year, even in the midst of winter, he wore leather-strap sandals on his bare feet. In a city known for its couturiers, where women wore yards of fabric over tightly-fitted corsets and men’s collars reached up to their chins, Duncan appeared naked to many stunned observers.

–

Duncan’s unusual lifestyle extended beyond his sartorial choices. He presented himself as an instructor in his own theory of movement (kinematics) and brand of philosophy (actionalisme), which he taught at his Akadémia on the rue de Seine in Paris’s sixth arrondissement, near the École des Beaux-Arts. Duncan also preached simplicity of diet. His approach to the plate may have shocked Parisians even more than his dress.

A journalist for Paris Soir quizzed Duncan about his advocacy of natural foods. Duncan explained that he ate lettuce, celery, beets, turnips, walnuts, almonds, and fruit. When you are hungry, lettuce suffices? The journalist asked doubtfully. Absolutely, Duncan answered, a plate of lettuce and beans (haricots) was all he required. He had not eaten meat since the Duncan family paid a visit to Chicago, en route to Europe, where Duncan witnessed the grotesqueries of the abattoirs. I consider myself a man of sensibility and a lover of art, the journalist protested, but still I take pleasure in eating horse, partridge, and hare. Your sensibility is not fully developed yet, Duncan explained, no doubt handing the journalist a couple invitations to one of his Wednesday nights salons at the Akadémia.

–

Duncan’s Akadémia attracted many interested Parisians. He offered instruction in weaving and sandal-making (selling the products at two stores he eventually opened, one on the Left Bank and one on the Right Bank). He presented evenings of theatres, staging concerts of Greek songs, and dance performances. He offered special lectures on a range of subjects from philosophy to la sexualité de l’avenir (the sexuality of the future). What the sexuality of the future would consist of is not entirely clear, although the title of another lecture La Laicisation de la Polygamie et du Mariage suggests that Raymond, like Isadora, may not have believed in conventional marriage. The acolytes he attracted to the Akadémia and to Neuilly were mostly young women, many of them unwed mothers who brought their children along with them; la laicisation de la polygamie? After Penelope’s death from tuberculosis in 1925, Duncan married one of his students, Aïa Bertrand.

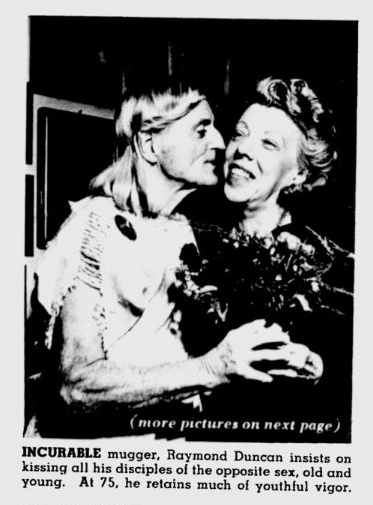

It seems likely that Bertrand was not the only of his disciples to attract Duncan’s amatory affections. Actionalisme, apparently, did not include simplicity in the affairs of the heart. At a 1925 conference Duncan organized, a crowd of female former students mobbed the stage and hurled complaints against Duncan. “Nous allions vers lui avec l’espoir de trouver de la beauté, de la bonté. Nous n’avons trouvé que la mauvaise foi, le mensonge, la violence, l’hypocrisie,” one of the students explained to a journalist who was present. We came to him in the hopes of finding beauty and goodness. We found only bad faith, deceit, violence and hypocrisy. Among their allegations, the protestors alleged that Duncan had cast pregnant students out of the Akadémia, telling them they were disgusting to him. Who impregnated the young women was unclear, although the protestors also alleged that Duncan had promised to adopt the children as his own then did not.

–

These stories resonated with Kay Boyle’s account. Boyle became pregnant around the time that she lived with Raymond and Aia Duncan in Neuilly, and although she claimed in her memoir to be uncertain about who the father was, circumstantial evidence points to Raymond Duncan as one possibility. In particular, Boyle’s decision to abort rather than carry the child, suggests a desire to destroy any ties with a man she had come to detest. (Another possible candidate for father was the crazy wealthy sun-worshipper Harry Crosby, who paid for Boyle’s abortion and died soon after in an infamous murder-suicide.) Boyle also concurred that the children being raised communally at Neuilly were neglected, going without shoes or socks even in the winter, sleeping in a barn without beds, and often going hungry while Duncan took taxis around Paris making appearances at elite social events. Even Menalkas Duncan endured this treatment. When the family visited North America in 1910, child welfare authorities in New York City temporarily seized five-year old Menalkas from his parents because of his underdressed state.

In 1921, when Menalkas was fifteen years old, he ran away from his father’s house for a week in protest against his upbringing. The newspapers had a heyday with this story, which they considered to be une affaire bien Parisienne (a very Parisian affair), perhaps because of its salaciousness. After Menalkas’s disappearance, Raymond plastered the walls of Paris with posters, produced on his own printing press with his own custom-designed font, denouncing a former friend, the industrialist Robert Bourbeau, for having seduced away his son. Bourbeau, according to Raymond, was a ravisseur de son fils.

Called before a judge, Menalkas testified that he had left his father’s home voluntarily, with the aid of Bourbeau, because he no longer wished to wear his hair long and to dress in togas and sandals. Journalists gleefully described Menalkas’s courtroom appearance, dressed in the most recent Paris fashions, apparently enjoying the conveniences of modern life. The judge found that Raymond Duncan’s complaint was groundless, and fined him 10,000 francs for defamation of Bourbeau. Soon Menalkas returned home and the two Duncans reconciled.

–

Later Menalkas moved to Provincetown, the artist community at the tip of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, where he sold sandals like those made by his father. Provincetown was also home to another former Duncan acolyte, Roger Rilleau, who (according to my grandmother) sold Duncan sandals out of the back of a truck, where he lived with his children. It was from Rilleau that my grandmother, visiting Provincetown for the summer, bought a pair of Duncan sandals in 1952 that lasted her for years. I only learned about my Grandmother’s Duncan sandals this fall, when she emailed me after I mentioned Raymond Duncan in my blog post about Kay Boyle. Even more amazing, my mother followed up with the memory that both she and my grandmother had in fact met Raymond Duncan himself, in Paris, in 1965, a year before his death!

My grandmother, my mother, and my mother’s cousin Rebecca and friend Patty were visiting Paris for a week (my grandparents lived in Britain throughout the 1960s), and my mother’s cousin wanted to buy a pair of sandals like my grandmother’s, which had held up remarkably well over the intervening decade. So the trio went to pay a visit to Duncan’s store, which still remained open. They ordered a pair of sandals (each pair was traced to the buyer’s foot and made to order), and were subsequently invited to one of the evening salons still held by Duncan and his decrepit acolytes. They accepted the invitation, and experienced one of the creepiest evenings of their collective lives. As one journalist wrote in 1949, fifteen years before my grandmother and the girls visited, “Duncan followers are mainly aging maiden ladies.” In 1965, the audience had become that much older, a crowd with one foot in the grave, living in a dimly remembered golden past when Duncan still commanded the adulation of many. After enduring several performances of unendurable singing and dancing, my grandmother and the girls fled as soon as they could. Unfortunately, Patty’s sandals did not prove to be of the same quality as those made by Rilleau, whom they learned had been through a terrible falling out with Duncan (the Duncanites were very upset that my grandmother had bought from Rilleau).

–

Strangely this is not the only intersection bringing Raymond Duncan’s life and mine together. I too once owned a pair of Duncan-style sandals, which I bought at Native Leather, on Bleecker street in the West Village, when I was around 14 or 15. I’m not sure where Native Leather’s owner, Dick Whalen, learned to make the sandals, but I’m sure it must have been through some connection to Duncan, possibly through Menalkas Duncan, who instructed Barbara Schaum, another sandal-maker in the Village, who is still in business today (as is Native Leather).

And if that’s not coincidence enough, I learned through my research yesterday that Raymond Duncan used to live on our very street in Paris, the rue d’Alésia, when he, Penelope, and Menalkas first arrived in Paris. This was actually their second address after they were kicked out of their first apartment, near the Eiffel Tower, for indecency (those naked arms and feet). Apparently, Duncan found “une maison plus hospitalière aux fantasies vestimentaires” (a house more hospitable to fantastic dress) on the rue d’Alésia. Not sure of the exact address.

The last time I encountered this many coincidences in the research process I felt compelled to write a book. (The story of how I came across Charity and Sylvia’s story is told in the preface.) Some people whom I have spoken to suggest that I should do the same for Raymond Duncan. But I fell in love with Charity and Sylvia, and I can’t say the same for Duncan.

Fascinating. But, yes, Raymond would be hard to love.

exceptional post, as usual… it made me laugh when you say he left his father’s home bc he “no longer wished to wear his hair long and to dress in togas and sandals”. 🙂

Excellent piece! Do you know any more about the Duncan shops in Paris? Specific locations or any extant collateral or images?

there were two shops, one on the right bank and one on the left. there are certainly images of the shops in old newspaper clippings. not sure what else might be out there. good question!

Enjoyed reading your article on Raymond Duncan. I lived with his grandson in France, who was Menalkas’s son. We were very close friends and I lost contact with him and am trying to get in touch with him if you have any clue of how to do that. Thanks very much. You can emails or Call me at 703-759-1994. I live in Maine. Janet Slade

Great to hear from you Janet. I would love to hear about what Menalkas’s son told you about the family. Please get in touch if you have any stories you would like to share. My email is rachel@cleves.net. Unfortunately I don’t have any contact information for the family. Good luck in your search.

What was the name of this son of Menalkas’s? Menalkas’s daughter is my grandmother Audrey and as far as I know she was an only child. Are you sure this grandson was not one of Raymond’s daughter Ligoa’s sons? I have spent years on and off again researching my family and have never came across this information. Maybe I can help you with your search as I am still in contact with Audrey and Ligoa.

Scott, have you tried getting in touch with Janet Slade? (phone number above). All I know of Menalkas’s son is the message that she left here.

I’m very curious what stories of Raymond you may have heard from your grandmother Audrey or from Ligoa. Did you ever meet your great-grandfather Menalkas? Feel free to get in touch with me at rcleves@uvic.ca

Wow, hi Scott! You and I have never met, but Audrey is my grandmother (my Nana) as well, meaning I would be your cousin, Hilary (Carol Anne’s eldest). Sort of neat to “meet” you here!

Best,

Hilary Gayle

My, call the subject of your book a creep right off the bat. You seem not to seek to understand, but to judge and condemn. Not a book I’d ever read. Prejudiced from the start…

I call ’em like I see ’em.

we have two paintings supposed to be by nephew of isadora duncan, just signed duncan, could these be by menalkas Duncan I wonder?

seamus

How cool. I’d love to see images of the paintings. How did you acquire them?