When Isadora Duncan’s mother was pregnant with the dancer, she could eat only iced oysters and iced champagne. Isadora danced her first dances in the womb, she claimed, under the influence of those effervescent bubbles and slippery molluscs. And she kept right on drinking champagne and dining on luxuries until her dying day. She would buy buckets of champagne to drink with friends even when she was too broke to rent a room where she could spend the night. Better just to stay up till dawn drinking.

A self-described bacchante, Isadora gave herself to the pleasures of the body with the same abandon as those erstwhile priestesses of Bacchus. “I have never ceased to be madly in love,” Isadora wrote in her memoir My Life, a chronicle of her countless erotic encounters, as much as a narrative of her evolution as a dancer. At twelve years old she read George Eliot’s Adam Bede and decided that she would “live to fight against marriage and for the emancipation of women.” She practiced what she preached, throwing herself ecstatically into affairs, whether for a night or for a year. “Some people may be scandalized,” she conceded, “but I don’t understand why.” As far as Isadora was concerned, she never felt herself to be guilty of any sin or impropriety. She was unafraid to appear ridiculous for her appetites, and she disdained “the conclusion formed by so many women that, after the age of forty, a dignified life should exclude all love-making.” Imprinted in the womb by her mother’s taste for the food of Aphrodite, Isadora kept drinking at the fountain of love until the moment in her fiftieth year when, driving to an afternoon’s assignation, her colorful shawl caught in the axel of her car and strangled the life from her.

She wore the evidence of her appetites, in the form of plump arms and calves, round belly, and soft chin, with grace and pleasure. She regarded her body as a vehicle for beauty, famously discarding the corsets and stockings that bound nineteenth-century women (even dancers) in exchange for loose tunics, bare legs, and bare feet. She danced from sylph-like adolescence into widening womanhood, through three pregnancies and into the heaviness of middle age. “I am glad,” she wrote, “that I was young in a day when people were not self-conscious as they are now; when they were not such haters of Life and Pleasure.” She was grateful to have come of age during an époque when “thinness was not equivalent to spirituality.” Isadora’s favorite photographs of herself were those taken by New York photographer Arnold Genthe after World War I, when she was already in her late thirties and far from the height of her popularity as a dancer. His photographs, she believed, were not “representations of my physical being but representations of conditions of my soul.”

–

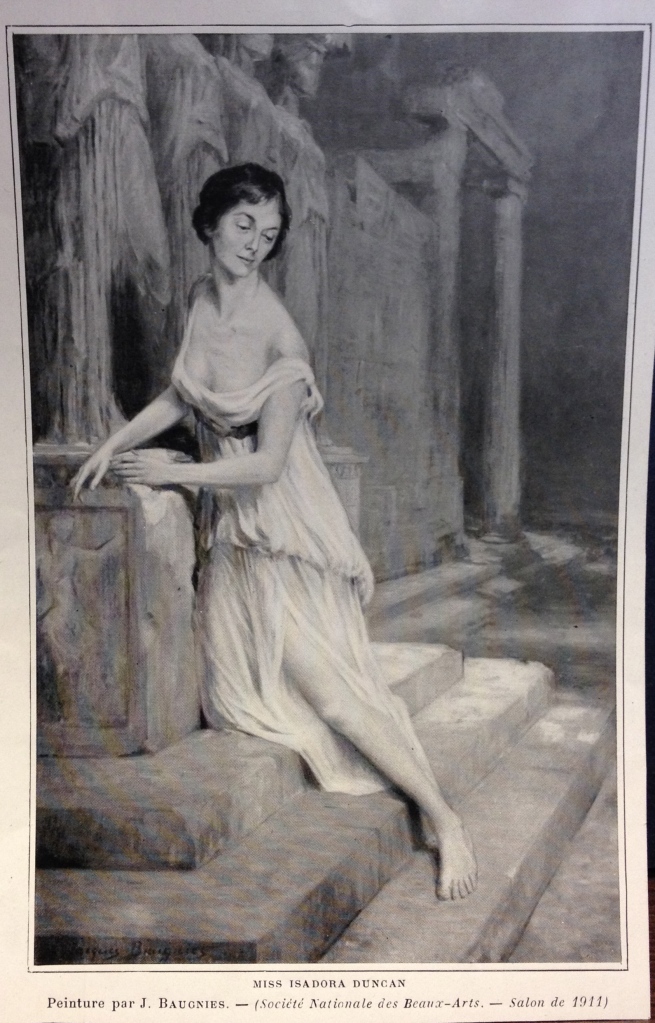

Of course, not everyone shared Duncan’s and Genthe’s vision. Many who idolized Isadora closed their eyes to her earthy appetites, substituting a purified and – not coincidentally – slimmed-down image of the dancer. The French painter Jacques Baugnies, who first met Isadora in London at the turn of the century, presented a portrait of his friend at the 1911 Paris salon des beaux-arts that refashioned her according to the emerging modern aesthetic for scrawny women. In the portrait, the skin pulls tightly across the dancer’s chest, revealing shadows of ribs that never made their appearance on Isadora’s corporal form, even in her more slender youth.

–

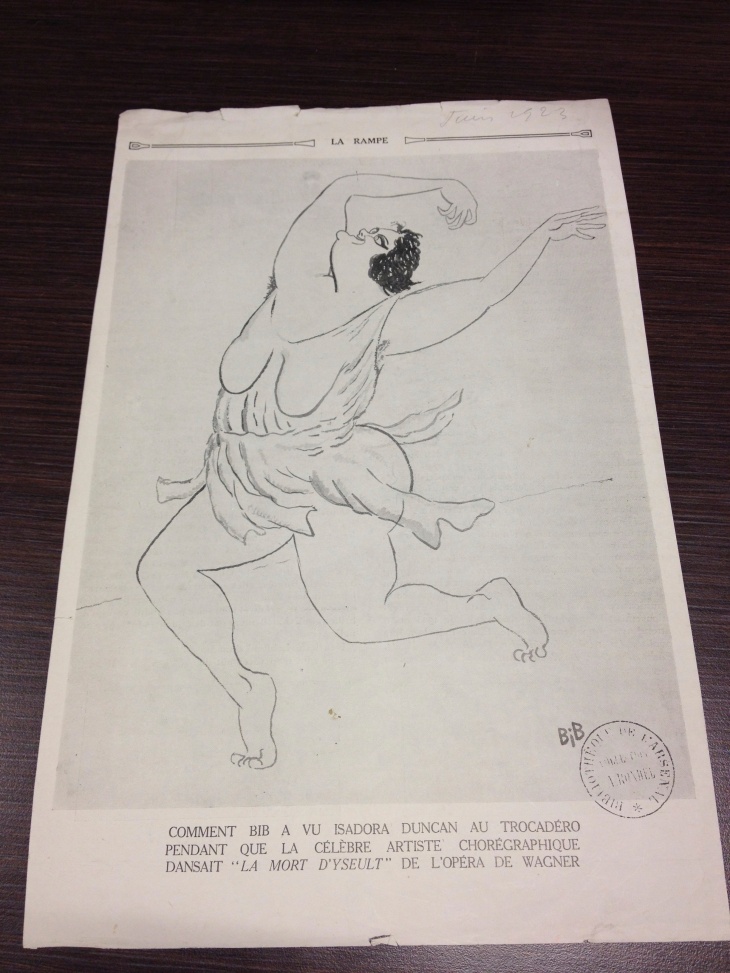

Detractors inflated Isadora’s corpulence and absurdity, seeing Isadora’s appetites all too clearly, but perceiving nothing of her grace. Bib, a caricaturist for the Paris humour magazine Le Charivari, drew a sketch of Isadora following her 1923 performance of “La Mort d’Yseult” (the death of Isolde) at the Trocadéro in Paris, which depicted the dancer as a ludicrous figure with pendulous breasts, a piggy nose, and a fat neck, clad in an indecent tunic.

–

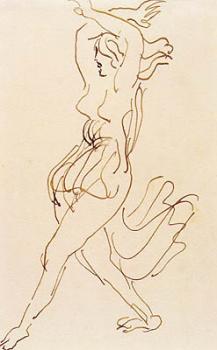

Like any good caricaturist, Bib captured more than a grain of truth in his unflattering portrait. Isadora did have a small pointed nose, she did have large breasts and a double chin, and she did have thick legs which held up a solid body, which she moved with such fluidity that the French artist Antoine Bourdelle regarded her as “une sculpture vivante,” a living sculpture. Bourdelle’s sketches of Duncan capture her thick thighs, round arms, and heavy breasts, and also her incredible fluidity of movement that entranced audiences for decades.

–

Isadora Duncan’s body inspired countless representations, idealized, disparaging, and honest, but these images are not the only way to reckon with the meaning of her story. She left behind more than an impression captured in the eyes of others; she recorded her own sense of self in her deeply reflective memoir. Although her life had been more exciting than a movie, as she boldly promised in the memoir’s second sentence, she was not content to give a mere recounting of her adventures. She aspired to the same honesty of expression in her writing that she delivered in her dancing. She wanted readers “to be able to clothe with flesh the skeleton that I have presented.”

My Life offers a fascinating account of the struggles that Isadora faced as a woman artist at the turn of the twentieth century. Her commitment to her artistry destroyed her relationships with many lovers, who wanted her to abandon the stage for domestic life. Being an artist also required her to leave her young children (conceived outside of marriage, each with a different lover) for long spells during their infancies and early years. The price Isadora paid for this choice proved more terrible than she could anticipate. A tragic car accident in 1913 drowned her first two children in the Seine before the older had turned ten. Isadora would never be able to make up the time she had missed during the children’s early years. Soon after she conceived a third child, born at the outbreak of World War I, who died shortly after birth.

Although she never recovered from the grief of her children’s deaths, during her final decade and a half Isadora devoured life with the same hunger she had shown all along. She travelled through Europe, Egypt, South America, North America, and the Soviet Union, conducting love affairs, swilling champagne, starting new ventures, and spending herself into penury. Worried about her extreme poverty, Isadora’s friends encouraged her to write a memoir and earn some money to live on. If she had lived to profit off her memoir, she would without doubt have blown the money on champagne and parties, as she had all her previous earnings. The memoir was unlikely to have been her redemption, instead it became a fabulous present to posterity. This blog post has just scratched the surface. If you have time to read My Life, then do.

Reblogged this on drifters bar grill + detox center and commented:

My kind of girl, I think.

Thank you for the reading tip. Once I had read her biography, I couldn’t find much about her on the internet. I suppose she is no longer so well known as she once was but I would have liked to get a point of view on her from those that knew her. She is so egotistical in her memoire—one would have liked to know if others found her discussions of her “Art” as engrossing.